International climate finance provided as part of Finland's development cooperation should also promote gender equality and help empower women and girls. Generally, climate finance projects have a positive impact on the status of women and girls in the partner countries. However, there are major differences in the impact of projects, and the information available on the impact also varies. This briefing paper is mainly based on the National Audit Office’s performance audit ‘Finland's international climate finance - Steering and effectiveness’ (6/2021), which examines the prerequisites for the effectiveness of Finland’s international climate finance.

Summary and conclusions

Promoting gender equality is one of the key principles of the Paris Agreement. Strengthening gender equality, empowering women and girls and urgent climate action are also included in the goals of the UN’s 2030 Agenda for Sustainable Development. Additionally, strengthening the status of women and girls is one of the four priorities of Finnish development cooperation, and gender equality is one of its four cross-cutting objectives. Therefore, international climate finance included in Finland’s development cooperation should not only support climate change mitigation and adaptation but also promote gender equality and contribute to empowering women and girls. This would also increase coherence and synergies between the goals of the 2030 Agenda.

The Ministry for Foreign Affairs has aimed to promote gender equality in all development funding, including climate finance, and has drawn attention to it in the goal setting of many programmes and projects. Generally, climate finance projects have a positive impact on the status of women and girls in the partner countries. However, there are major differences in the impact of projects, and the information available on the impact also varies.

The gender equality impacts of climate finance can only be verified if they are assessed and monitored systematically at different stages of the projects. For example, the documents related to the Private Forestry Project in Tanzania and the Water, Sanitation and Hygiene project in Ethiopia indicate that the gender impacts of bilateral climate finance projects have been monitored and reported in both qualitative and quantitative terms, using indicators that describe women’s status. In general, they show that women’s status has improved, even if progress has at times been slower than intended.

Finland has actively promoted and monitored gender equality objectives in the funds under the climate conventions. While Finnfund and the Energy and Environment Partnership Trust Fund for Southern and Eastern Africa (EEP Africa) monitor the realisation of gender equality at project level, the results are reported at portfolio level. Little attention has been paid to gender equality issues in the Finland-IFC Blended Finance for Climate Program, even if some of its projects have produced gender equality plans.

While gender equality has played a minor role in concessional credit projects, an assessment of gender equality impacts is required as part of project plans in the PIF instrument set up to replace this scheme.

Climate change and climate action have an impact on gender equality

Climate change affects vulnerable groups of people particularly hard. Women and girls are in a special position because

most people living under the poverty line are women and girls,

especially in developing countries, women’s livelihoods are often linked to water as well as agriculture and forestry, which are particularly dependent on a stable climate, and

the uneven distribution of capital and economic resources between women and men means that women in developing countries, in particular, have less opportunities to prepare for and adapt to climate change than men[1].

Climate change mitigation and adaptation measures affect individuals and the structures of society. The impacts on women’s and girls’ living environments vary and may also differ from men’s experiences.

The impacts of climate change on the status of women and girls are clearly identified in the goals of the UN’s 2030 Agenda for Sustainable Development[2]. While Goal 5 aims for gender equality, its indicators make no reference to climate action. Goal 13 encourages taking urgent action against climate change and its impacts. One of its five targets has a particular focus on women, youth and local and marginalised communities. Identifying links between the sustainable development goals is important in creating policy coherence among them and in aiming at the effective implementation of the UN Agenda 2030[3].

In international climate conventions, gender equality has emerged as an essential part of the work against climate change in recent decades. The UN Framework Convention on Climate Change (UNFCCC, 1992)[4] does not contain any reference to the gendered effects of climate change or the status of women. In the Paris Agreement (2015)[5], the Parties undertake to address gender equality and women’s rights in climate action. Under the Paris Agreement, the adaptation and capacity building required by climate change should be gender responsive.

At the Conference of the Parties to the climate conventions (COP25) in 2019, the Lima Work Programme[6] and a five-year action plan associated with it[7] were adopted to promote gender equality in the implementation of climate agreements.

Climate finance is one instrument for fulfilling the gender equality commitments of the climate conventions. Under the climate conventions, the industrialised countries have committed to providing financial resources to developing countries to advance mitigation of and adaptation to the effects of climate change.

It is important for policymakers to understand the structures that create and maintain gender inequality. This will help to promote equality when targeting and implementing development cooperation projects, including climate finance. Implementing climate finance projects without meaningful participation of women will risk their effectiveness, and projects can even aggravate existing inequalities[8]. In this light, increasing the gender-responsiveness of climate finance is an opportunity to improve the effectiveness, efficiency and sustainability of investments[9].

The impacts on gender equality of climate finance projects can be anticipated and taken into account in many ways already in the planning phase[10]. In many development cooperation projects, a gender analysis and an action plan for promoting gender equality are produced in the planning phase. This helps to identify the projects’ potential risks to and opportunities for promoting gender equality. However, analyses and plans are not enough on their own, and it is important that projects have access to sufficient competence to implement the plans.

Improving the status of women and girls is one of the key objectives of Finland’s development policy and climate smart foreign policy

The objectives of Finland’s development policy and climate smart foreign policy are in line with the UN’s Sustainable Development Agenda and commitments made under international agreements. Gender equality objectives are high on the agenda of Finland’s development policy[11]: improving the status of women and girls is one of its four priorities. Both Prime Minister Marin’s Government Programme[12] and the Government Report on the Implementation of the 2030 Agenda[13] note that systematically promoting gender equality and the full realisation of girls’ and women’s human rights is a key objective of Finland’s foreign and security policy. The Government Programme states that 85 percent of new development cooperation projects should have gender equality as a primary or a secondary target, or have it mainstreamed in line with the OECD definitions.

Gender equality is also one of the four cross-cutting objectives of Finland’s development cooperation. Consequently, special attention is paid to equality in all development cooperation activities, rather than exclusively in gender equality work.[14] In the cross-cutting objectives of development cooperation, gender equality work is based on the UN Convention on the Rights of Women. This means that gender equality is primarily promoted in development cooperation by empowering women. While climate resilience and low-emission development are separate cross-cutting objectives, they are interlinked with other objectives as well. For example, climate change and climate action can have many types of impacts on human rights and gender equality.

Finland’s Action Plan for Climate Smart Foreign Policy[15] notes that addressing gender equality and participation of all population groups in planning and implementing climate action will improve its efficiency, impact and sustainability. Additionally, women play a key role as actors and agents of change in climate change mitigation and adaptation. According to Finland’s Development policy results report (2018)[16], in Finnish development cooperation measures aim to ensure that climate policy and action also promote gender equality, while gender equality also makes climate action more effective.

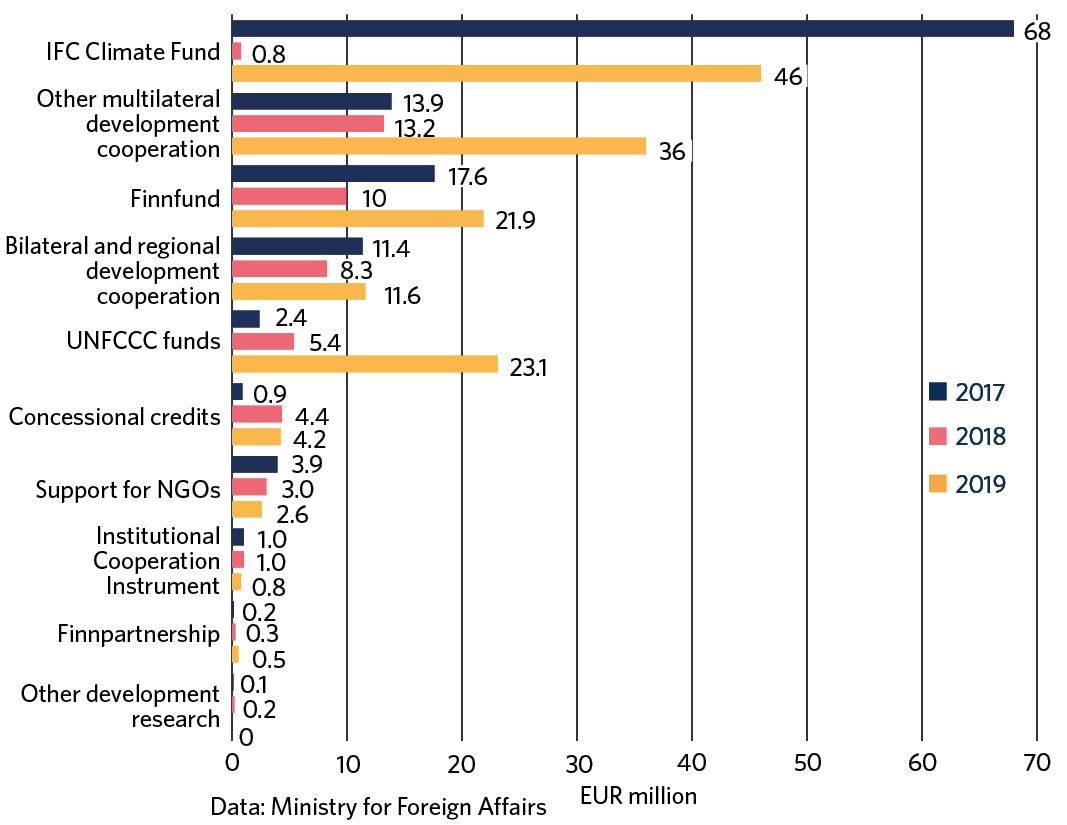

Finland’s international climate finance is part of the official development cooperation administrated by the Ministry for Foreign Affairs. Nearly all funding channels, forms and instruments of development cooperation are used in Finland’s climate finance (Figure 1). This briefing paper examines how gender equality is addressed and promoted in Finland’s international climate finance in the light of the following examples:

funds under the climate conventions: Green Climate Fund (GCF) and Global Environment Facility (GEF)

Finland-IFC Blended Finance for Climate Program

Finnfund’s climate finance

Concessional credits

Bilateral and regional development cooperation: Private Forestry Project in Tanzania; Water, Sanitation and Hygiene project in Ethiopia; and Energy and Environment Partnership Trust Fund for Southern and Eastern Africa.

Ministry for Foreign Affairs has promoted gender equality in climate convention funds

Together with the other member states in its constituency, Finland has actively promoted gender equality in climate convention funds, such as the GCF and the GEF. The funds’ objectives and indicators of gender equality are important because they contribute to ensuring that the use of Finland’s funding contributions aligns with the priorities and cross-cutting objectives of the national development policy.

The GCF’s intent of promoting gender equality is evident in the fund’s results management framework, where results should be disaggregated by gender whenever appropriate[17]. In addition, the GCF requires that the implementing organisations produce both an assessment of the initial state of gender equality in the partner region and an action plan for promoting equality through the project[18]. All GCF projects have assessed their impact on gender equality. However, Monitoring the results of gender equality work is challenging because the implementing organisations do not always provide adequate reports on the progress and results of gender equality plans.[19]

The objectives and operations of the GEF have a clear focus on gender equality, and it is monitored systematically. Between 2014 and 2018, 66 per cent of GEF projects produced some type of gender analysis[20]. In May 2017, the GEF Independent Evaluation Office published an evaluation[21] of gender mainstreaming in the fund, and the Council meeting of December 2017 adopted an updated policy on gender equality[22]. An evaluation of Finland’s multilateral development cooperation published in 2020 notes that the Ministry for Foreign Affairs cites the GEF’s gender equality policy update as an example of Finland’s successful influencing of the theme. The evaluation found that gender mainstreaming in the GEF shows modest improvement over the previous OPS period, especially since the first policy on gender equality was published in 2011. Under the updated policy on gender equality, GEF must collect sex-disaggregated data and incorporate sex-disaggregated targets and gender-sensitive indicators in monitoring, evaluation and reporting of relevant activities. While no target level has been set for gender equality, it is one of the separate reporting targets in GEF’s corporate scorecard for 2020[23]. Estimates hold that at the end of the year 2020, gender mainstreaming in GEF projects had achieved a relatively good level: 51 per cent of project beneficiaries were men and 49 per cent were women.

Finland-IFC Blended Finance for Climate Program has paid little attention to gender equality

In recent years, the share of development policy investments in Finland’s climate finance has increased significantly. According to the Ministry for Foreign Affairs’ Development policy investment plan (2019)[24], a minimum of 75 per cent of the investments will be allocated to climate finance. Gender equality is to be supported by allocating 85 per cent of the funding to projects with gender equality objectives. Promoting women’s entrepreneurship is a special priority for the appropriation for development policy investments.

Among other things, the appropriation for development policy investments has been used for climate finance by establishing the Finland-IFC Blended Finance for Climate Program[25]. The International Finance Corporation (IFC) is a member of the World Bank Group. The fund is to monitor the realisation of gender equality based on the employment impacts of its investments, disaggregated by gender[26]. However, the annual reports for 2018 and 2019[27] did not yet use the indicators specified in the Program Document to report on the results. Additionally, the project documents submitted to the IFC Board have not assessed the projects’ gender equality impacts. Nevertheless, a Gender Action Plan[28] has been drawn up for the fund’s hydropower project in Nepal, for example, with the aim of promoting women’s participation in the project and ensuring it does not have negative impacts on women or their status in society. The implementation of the Gender Action Plan is to be monitored regularly in cooperation with the project’s partner community. No information on results is available as yet.

Finnfund monitors women’s status in its partner companies

Development policy investments have been channelled through Finnfund, and Finnfund also uses other government funding for its investments. Finnfund’s Gender Statement (2019)[29] stresses the promotion of gender equality and, in particular, the status and rights of women and girls. Finnfund’s Annual Report 2019 highlights the introduction of the Gender Statement as one of the key successes of the year. Finnfund’s objectives state that generally all new investments must contain objectives that promote equality or meet the criteria of development funding institutions’ initiative ‘2X Challenge – Financing for Women’. Consequently, Finnfund develops its funding principles and tools, ensuring that they direct investment decisions to support these priorities. As a part of Finnfund’s ownership steering, the Ministry for Foreign Affairs has monitored the attainment of gender equality targets since 2019 based on the share of women in the employees of Finnfund’s partner companies (2019: 38%) and the share of partner companies owned by women (2019: 1%). Additionally, Finnfund monitors and reports on the share of women in the decision-making bodies of partner companies (2019: 15%) and leadership (2019: 25%)[30]. Even though the share of partner companies owned by women is small, women account for the majority of smallholdings and borrowers supported by Finnfund.

Practical tools in Finnfund’s gender equality work include promoting equality in the workplace, supporting women’s entrepreneurship and professional development, and providing micro credits and financial services to women[31]. In 2019, the Finnish government granted Finnfund a €210 million convertible bond from financial investment appropriation, half of which is allocated to projects combating climate change and the other half to support the status of women and girls in 2020–2021[32]. By the end of 2019, Finnfund had invested €57 million in seven equality projects and €49 million in seven projects that promote climate change mitigation and adaptation[33]. As Finnfund has so far not submitted a report to the Ministry for Foreign Affairs on its climate change and gender equality impacts itemised by individual investment, no information was available on the extent to which Finnfund’s climate finance has promoted equality, or equality funding has created climate benefits.

PIF projects focus more on equality than previous concessional credits

Concessional credits are export credits granted to developing countries whose interests are paid out of development cooperation funds. Their purpose has been to support exports of Finnish technology while promoting economic and social development in developing countries. The concessional credit projects have largely come to an end, as the last one was initiated in autumn 2017. However, interest subsidies will continue to be paid for a long time, as the last payments are due in 2028.

The Ministry for Foreign Affairs’ policies and guidelines on concessional credits do not address gender equality. An evaluation of the Finnish concessional aid instrument[34] published in 2012 found that the concessional credit projects have generally paid very little attention to gender issues. Several examples show that the appraisals of gender impacts in concessional credit project documents have been superficial, and they have not been monitored systematically by the Ministry for Foreign Affairs.

According to the guidelines for the Public Sector Investment Facility (PIF) established in 2016 to replace the concessional credit scheme, gender equality impacts must be assessed in project plans. Only one PIF project has been approved for funding[35] so far, and there is no information on its results as yet.

Energy and Environment Partnership Trust Fund for Southern and Eastern Africa aims for equality

The purpose of the Energy and Environment Partnership Trust Fund for Southern and Eastern Africa (EEP Africa) administrated by the Nordic Development Fund (NDF) is to provide early-stage risk financing for projects that promote renewable energy and energy efficiency, thus improving the actors’ possibilities of obtaining further financing from other funding providers. Additionally, the general objective of EEP Africa is to promote the UN’s Sustainable Development Goals, including Goal 5 (gender equality). According to its rules, gender equality is one of the selection criteria for projects, and themes that promote gender equality can be emphasised in the calls for proposals[36]. For example, EEP Africa’s call for proposals in 2019 was specifically aimed at projects promoting gender equality[37]. EEP Africa complies with the NDF ‘s gender equality policy, which entered into force in December 2020[38].

One of the goals of EEP Africa is that women’s share in the management of partner organisations would be at least 40 per cent, and that women would account for at least 50 per cent of their employees. In 2019, women accounted for 47 per cent of the management and 46 per cent of the employees of partner organisations in EEP Africa’s active project portfolio. According to the annual report, several projects promoted the Sustainable Development Goal of gender equality.[39]

The mid-term evaluation of EEP Africa published in 2020 notes that while the fund has taken concrete steps towards empowering women and girls in its projects, the actual gender equality impacts of the projects may not have been realised yet or may require additional work and resources to be realised. The mid-term evaluation recommends that the fund should further strengthen its support for female entrepreneurs, for example by setting quotas for them in project selection.[40]

Bilateral climate finance is likely to have contributed to achieving both climate and gender equality objectives

Around half of Finland’s bilateral climate finance in 2017–2019 was allocated to forestry projects in Tanzania. The Private Forestry Project (PFP) in Tanzania has monitored the progress of equality based on women’s share in the beneficiaries and participant groups. The completion report of the project’s first phase[41] found that the project paid significant attention to gender equality. The results presented in the report indicate progress in some objectives but not in all of them: 27 per cent of the members in administrative bodies of the supported tree growers’ associations were women (target 40%, baseline 32%) and 53 per cent of the supported companies employed women (target 75%, baseline 29%). Tanzania Tree Growers’ Association requires that one third of its Board members are women and recommends the same rule for its affiliated organisations at the local level. While women’s participation brings additional resources to tree growing, the threat of physical and sexual violence restricts women’s access to the official economy, including forestry.[42] Examples from India and Nepal show how women’s participation in the management and governance of natural resources, including forests, leads to better conservation and regeneration, which in turn has positive climate impacts[43].

In 2017–2019, Ethiopia was the second largest partner country receiving Finland’s bilateral climate finance. The aim of phase three of the Community-Led Accelerated Water, Sanitation and Hygiene (COWASH) project was strengthening further the project’s work to build local water supply and sanitation systems in rural areas. During the three-year project, a safe and sustainable water system was built for 250 schools. These systems benefited approximately 126,000 pupils and school staff, 49 per cent of whom were girls and women.[44] The construction of water systems improves the status of girls in particular, as studies have found that the lack of facilities suitable for managing menstrual hygiene is a major reason for girls’ absence from school and dropping out of education altogether in Ethiopia and other developing countries[45].

Additionally, 221 health centres also applied for funding for water systems, and during the project these systems were built for 99 health centres. The main reason for the low number of implemented systems in comparison to applications was the prioritisation of community water projects and a lack of water resources near health centres. Reports note that more than 4,100 health sector employees benefit from the water system projects for this sector, of whom 50.4 per cent are women, but no impacts on patients have been reported.[46]

According to the final report[47] of phase three of this project, the share of women among water cooperative members increased from 33.3 per cent to 40.9 per cent during the project. The share of women in their leadership increased from 4.3 per cent to 10.5 percent during the project. While women’s status in the administration and leadership of water cooperatives has improved, social and cultural norms prevailing in households continue to restrict their participation.

The COWASH project produced instructions for identifying and managing social, environmental and climate risks with the aim of helping to address specific sensitivities associated with climate change in the water, sanitation and hygiene sectors. In addition, the preparation of climate sustainability and water safety plans for existing water supply systems was continued. The plans’ purpose was to ensure that the water services in the region are able to withstand the pressures caused by social, environmental and climatic changes. According to the project plan, women play an important role in ensuring this resilience. However, no reports were produced on the impacts of the climate sustainability and water safety plans and the role of women in preparing and implementing them.

[1] Schalatek, L. & Nakhooda, S.: Gender and Climate Finance.; OEDC DAC: Making climate finance work for women: Overview of the integration of gender equality in aid to climate change (pdf).

[2] Transforming our world: the 2030 Agenda for Sustainable Development.

[3] Weitz, N., Carlsen, H., Nilsson, M. & al.: Towards systemic and contextual priority setting for implementing the 2030 Agenda. Sustainability Science 13, 2018.; Weitz, N., Carlsen, H. & Trimmer, C.: SDG Synergies: An approach for coherent 2030 Agenda implementation (pdf). Stockholm Environment Institute 2019.

[4] United Nations Framework Convention on Climate Change (pdf). 1992.

[5] Paris Agreement (pdf). 2015.

[6] The Enhanced Lima Work Programme on Gender.

[8] United Nations Framework Convention on Climate Change. Introduction to Gender and Climate Change.

[9] Schalatek, L. & Nakhooda, S.: Gender and Climate Finance (pdf). 2015.

[10] Vainio-Mattila, A.: Navigating Gender. A framework and a tool for participatory development. Ministry for Foreign Affairs 2001.

[11] Ministry for Foreign Affairs. Finland’s development policy. One world, common future – towards sustainable development. Government report 2/2016 vp.; Ministry for Foreign Affairs. Report on Development Policy across Parliamentary Terms. Publications of the Finnish Government 2021:23

[12] Programme of Prime Minister Sanna Marin’s Government 10 December 2019: Inclusive and competent Finland – a socially, economically and ecologically sustainable society.

[13] Government Report on the Implementation of the 2030 Agenda. Towards a carbon-neutral welfare society. Publications of the Prime Minister’s Office 2020:7.

[14] Ministry for Foreign Affairs. Guideline for the Cross-Cutting Objectives in the Finnish Development Policy and Cooperation.

[15] Ministry for Foreign Affairs. Finland’s Action Plan for Climate Smart Foreign Policy.; Ministry for Foreign Affairs. Finland’s Action Plan for Climate Smart Foreign Policy (undated).

[16] Ministry for Foreign Affairs. Development policy results report 2018.

[17] Green Climate Fund. Integrated Results Management Framework (pdf). 2020.

[18] Green Climate Fund. Project Review: Gender.

[19] Green Climate Fund. Annual portfolio performance report 2018 (pdf); Green Climate Fund. Annual portfolio performance report 2019 (pdf).

[20] Global Environment Facility. Topics: Gender.

[21] Global Environment Facility. Evaluation on gender mainstreaming in the GEF (pdf). 2017.

[22] Global Environment Facility. Policy on Gender Equality, 31.10.2017 (pdf).

[23] Global Environment Facility. GEF Corporate Scorecard, December 2020 (pdf).

[24] Ministry for Foreign Affairs. Development policy investment plan 2020–2023.

[25] Ministry for Foreign Affairs. IFC Blended Finance for Climate Program.; International Finance Corporation. Finland – IFC Blended Finance for Climate Program.

[26] International Finance Corporation. Finland – IFC Climate Change Program. 1 September 2017.

[27] Finland-IFC Blended Finance for Climate Program: Progress Report, September 2019 (pdf).

[28] Gender Action Plan: Upper Trishuli-1 Hydropower Project, Nepal. Environmental Resources Management. Consultation draft report, March 2018 (pdf).

[29] Finnfundin tasa-arvolinjaus 29.3.2019 (pdf); Finnfund Gender Statement 29 March 2019 (pdf).

[30] Finnfund. Finnfund Annual Review 2020 (pdf)

[31] Finnfund. https://www.finnfund.fi/wp-content/uploads/2018/11/SDG-Finnfund.jpg.

[32] Finnfund. Finnfund’s climate investments 2019–2021.

[33] Finnfund. Finnfund Annual Review 2019 (pdf).

[34] Ministry for Foreign Affairs. Finnish Concessional Aid Instrument. Evaluation report 2012:4.

[35] Ministry for Foreign Affairs. PIF Ethiopia: Improving meteorological observation infrastructure & forecasting capabilities of the National Meteorological Agency. Funding decision 9 March 2018.

[36] Contribution Agreement between Ministry for Foreign Affairs of Finland and Nordic Development Fund in respect of Participation in the Energy and Environment Trust Fund. 9 March 2018.

[37] EEP Africa. New Portfolio Advances Women in Leadership.

[38] Nordic Development Fund. Gender equality policy 2020 (pdf).

[39] EEP Africa Annual Report 2019 (pdf).

[40] Altai Consulting. Impact and Performance Evaluation of EEP Africa, 26.10.2020.

[41] Participatory Plantation Forestry Programme (PFP2).

Completion Report of the first phase of the Private Forestry Programme, 27.6.2019.

[42] Talvela, K. & Mikkolainen, P.: Evaluation of the agriculture, rural development and forest sector programmes in Africa. Country report: Tanzania.

[43] Agarwal, B.: Gender and forest conservation: The impact of women’s participation in community forest governance. Ecological Economics, 68(11):2009.

[44] COWASH III 2009–2011 EFY Cumulative Performance Report.

[45] Tegegne, T.K. & Sisay, M.M.: Menstrual hygiene management and school absenteeism among female adolescent students in Northeast Ethiopia. BMC Public Health 14, 1118 (2014).; Belay, S., Kuhlmann, A. & Wall, L.: Girls’ attendance at school after a menstrual hygiene intervention in northern Ethiopia. International Journal of Gynecology & Obstetrics. 149:2020.

[46] COWASH III 2009–2011 EFY Cumulative Performance Report.

[47] Final Endline Survey Report for COWASH III Project, 30.5.2020.