Vivi Niemenmaa, Deputy Director at the National Audit Office of Finland (NAOF), worked for six years as a national expert at the European Court of Auditors (ECA). In this blog post, she shares some of her experiences with sustainable development and some of the eye-openers she had when providing SDG training in Bhutan and Kuwait.

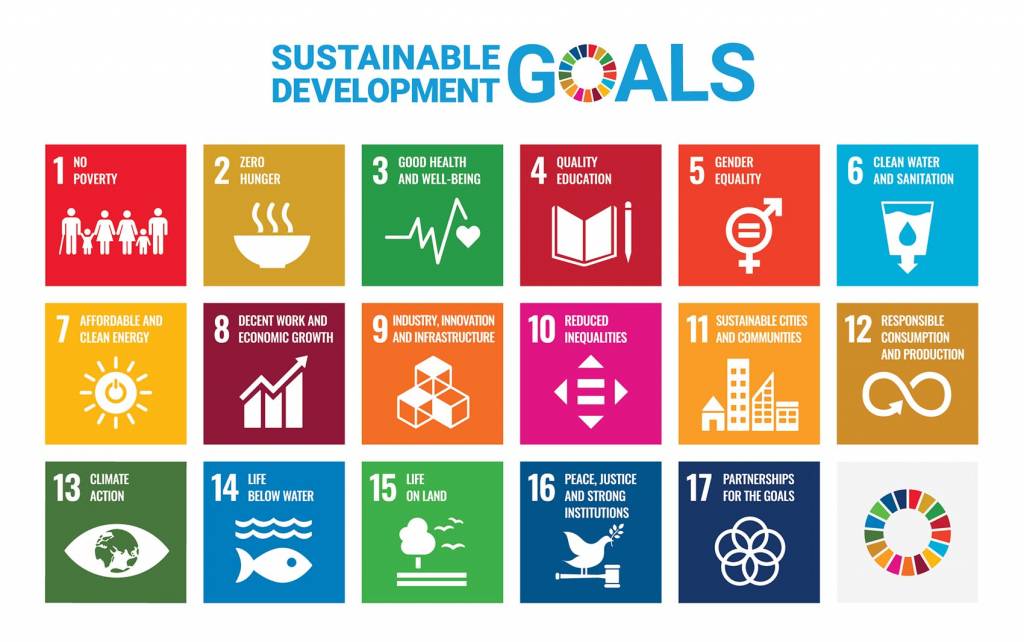

Over the twenty years that I have followed sustainable development discussions, global sustainable development policy has had its ups and downs. Nevertheless, it has been somewhat surprising to observe how vigorously Agenda 2030 and the 17 SDGs adopted by the United Nations in 2015 have been pushed to the centre of global discussions and, in many cases, of national policies. The SDGs successfully combine the more environmental policy-oriented Rio Process, launched in 1992, and the more development policy-oriented Millennium Development Goals. The SDGs provide clear policy goals and targets – and I would not underestimate the power of the outstanding iconography, either.

The International Organisation of Supreme Audit Institutions (INTOSAI) has integrated the United Nations Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs) in its 2017–2022 strategy. Individual supreme audit institutions (SAIs) are now considering how to include the SDGs in their audit planning.

However, not everyone is excited about the SDGs. As an auditor, you sometimes hear comments about whether anyone is really supposed to take the SDGs seriously. It is actually quite the contrary: the SDGs provide a good opportunity to hold governments accountable for papers signed in fancy meetings.

Some people find sustainable development too idealistic or vague. However, the sustainable development theory is not radical at all, as it accepts economic growth and believes in technological innovation. Sustainable development is a concept that tries to integrate various perspectives, time horizons and geographical scales. This is exactly what we need to solve serious problems.

The interest in the SDGs means that individual SAIs in different countries are yearning for more information about the topic. I conducted two training programmes on the SDGs for SAIs in July 2018. I delivered the first one together with Deputy Auditor General Marko Männikkö, and with the support of project adviser Outi Jurkkola, on behalf of the National Audit Office of Finland at the Office of the Auditor General of Bhutan. I held the second training programme on behalf of the ECA at the State Audit Bureau of Kuwait.

Examples and their local interpretation

When planning a training programme, it is relatively easy to collect policy and audit examples but more challenging to try to adjust sustainability issues to the local circumstances. Therefore I always try to stress that I speak from a European perspective, and on top of that with a Nordic world view, and ask the audience to challenge me if they find some of the examples strange.

Unlike the Millennium Development Goals, the SDGs are universal, which means that each country should interpret them in the context of their own country. For example, SDG 2 on zero hunger might at first glance seem less relevant for developed countries. However, upon further reflection, you soon realise that it addresses questions such as nutrition and sustainable agriculture. SDG 6 on clean water and sanitation can range from providing basic sanitation facilities to the development of next-generation wastewater treatment tackling traces of medication or micro-plastics, depending on the country’s situation and resources.

In Finland, the economic sustainability challenges relate to an ageing population and the dependency ratio. My Bhutanese colleagues, in turn, named their young population and youth unemployment as the biggest problem in their nation of 800 000 inhabitants.

Bhutan is a ‘carbon negative’ country, exporting large quantities of its hydropower to India. Kuwait, with four million inhabitants, has, in turn, almost 10% of the world’s oil reserves. At the time of the course, northern Europe was suffering from an unusual heat wave and forest fires. In the thoroughly air-conditioned buildings in Kuwait, a temperature of 47 degrees Celsius is not an issue. Compared with Kuwait, northern countries seem to be poorly prepared for extreme heat waves.

A critical question is how to address the carbon risk in such a context. The best I could do was to refer to the future risks related to fossil fuels, the investment principles for funds collected in future from oil revenues, renewable solar energy, and the effects that climate change is having on migration.

Where are the future generations?

You cannot talk seriously about sustainability without stressing the long-term perspective, and connecting the environmental, social and economic dimensions. I have noticed that SAIs do not pay sufficient attention to the long-term perspective. I find this worrying, given that future generations are at the very heart of the concept.

On the one hand, SAIs should ask their governments whether their sustainability aspirations include future-oriented thinking and long-term risk assessments. On the other hand, SAIs should ask themselves what the time-line is against which they do their assessments and give their recommendations. If you want to take sustainable development seriously, the next multiannual financial framework or the next five-year plan is far from sufficient.

In this context, one interesting example is the audit mandate of the SAI of Bhutan, the Royal Audit Authority, which covers all public funds and resources, including natural resources. This mandate is much broader than we are used to in the western audit tradition, and it is not limited by any organisational boundaries. It can also help widen the perspective from auditing annual expenditure to long-term considerations, perhaps to even including natural resources in the national accounts.

Surprising interconnections

My favourite part in providing sustainability training is the exercises on making interconnections and the discussion that this process facilitates. For instance, how are public health and fossil fuels interrelated? Well, at the end of the day the ease and convenience of moving around with fossil fuel-powered vehicles is making us fat in an increasing number of countries.

Air pollution is obviously costing us a huge amount in public health expenses. Why are governments paying so little attention to this, and why is the health sector so silent about these problems? Another example is the attempt to increase the use of renewable energy, which may have led to serious violations of human rights in developing countries through oil plant cultivation. Yet, one can ask: how transparent about this are the funds through which more and more global finance is flowing? And a final example: it is possible to mainstream gender issues into any policy area, as highlighted by the Swedish model of feminist foreign policy.

Sustainability awareness varies from country to country. Examples ranging from the monetary value of ecosystem services and the crucial economic significance of tiny little bees providing pollination services to the idea of gender or climate mainstreaming, or to the possibilities of SAIs acting as role models in green office practices can hopefully open our eyes to new ways of thinking – and auditing.

Four approaches to auditing the SDGs (INTOSAI Strategy 2017–2022):

Assess the preparedness of governments to implement the SDGs;

Undertake performance audits on key government programmes that contribute to specific aspects of the SDGs;

Assess and support the implementation of SDG 16, especially 16.6. on effective, accountable and transparent institutions, and SDG 17 on partnerships and means of implementation;

Be role models for transparency and accountability in their own operations, including auditing and report writing.

The blog post is a shorter version of the article published in ECA Journal 3/2019 (pdf)