The debt sustainability analysis will play a key role in the reformed debt rules. The preliminary calculations made by the fiscal policy monitoring function outline the need to adjust public finances in the coming years. Due to the significant impact of the framework, it would be desirable to have a broader social debate on the subject.

This post is the second part of a blog series. Read also the first part of the series: “The EU’s debt rules are being reformed – the focus will shift strongly to Member State-specific assessment”.

Such a large (and technical) reform of the rules naturally raises the question of how it will affect the fiscal policy of the different Member States.

This article presents preliminary calculations of the adjustments that Finland will have to make based on the reformed rules. The calculations focus on a situation where the length of the adjustment plan is only four years. A potential extension of the adjustment plan has not been taken into account.

It is not yet possible to make exact calculations, as the Commission will publish its updated debt sustainability analysis only later in the spring.

In the calculations, the four-year adjustment period covers the years 2024–2028 and the 10-year review period the years 2028–2038. The review period in the scenario that takes uncertainty into account is five years.

The calculations consider only the debt sustainability safeguard, as it is more relevant in the case of Finland.

In the calculations, the annual adjustment need is described by the change in the structural primary balance. The structural primary balance is the difference between revenue and expenditure (fiscal balance) less interest payments, taking into account the business cycle.

The change in the structural primary balance describes how contractionary the fiscal policy is. A greater change means a more contractionary fiscal policy.

A more significant adjustment is required if uncertainty is taken into account

Table 1 shows the adjustment needs produced by the scenarios used in the debt sustainability analysis. In the scenarios that ignore uncertainty, the most stringent annual adjustment required would be 0.25 percentage points. With the gross domestic product (GDP) projected for 2024, this would be about EUR 0.7 billion.

In the scenario of the Commission’s debt sustainability analysis that takes uncertainty into account, 70% of the simulated debt paths should be declining. The International Monetary Fund (IMF) (2022) uses an 80% probability as a “credibility level” in its analysis.

| Scenario | Annual adjustment need (pp. relative to GDP) |

Satisfies the debt sustainability safeguard? | Credibility level | Deviation modelling |

| Baseline trajectory | 0.11 | No | – | – |

| Unfavourable (structural) primary balance | 0.23 | No | – | – |

| Unfavourable r-g | 0.25 | No | – | – |

| Financial market failure | 0.11 | No | – | – |

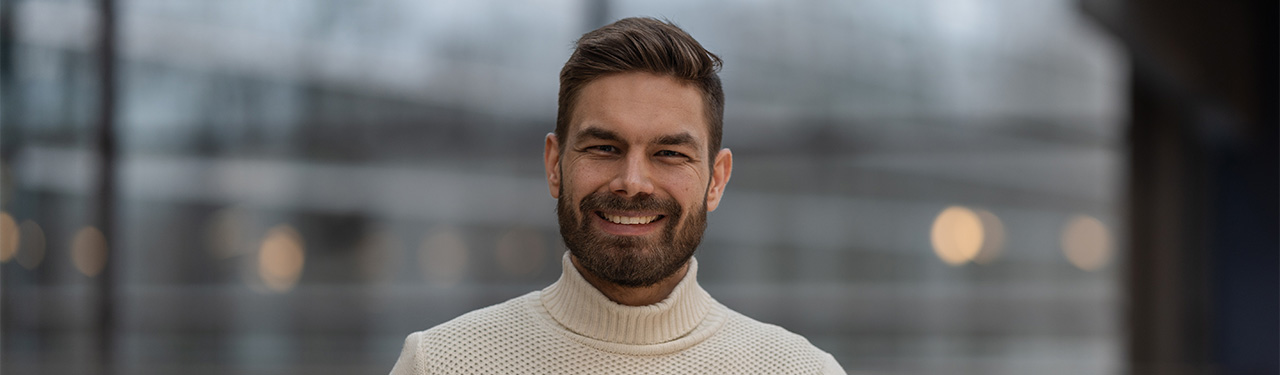

| Baseline trajectory (Figure 1) | 0.31 | No | 70% | N |

| Baseline trajectory | 0.46 | No | 80% | N |

| Baseline trajectory | 0.68 | Yes | 90% | N |

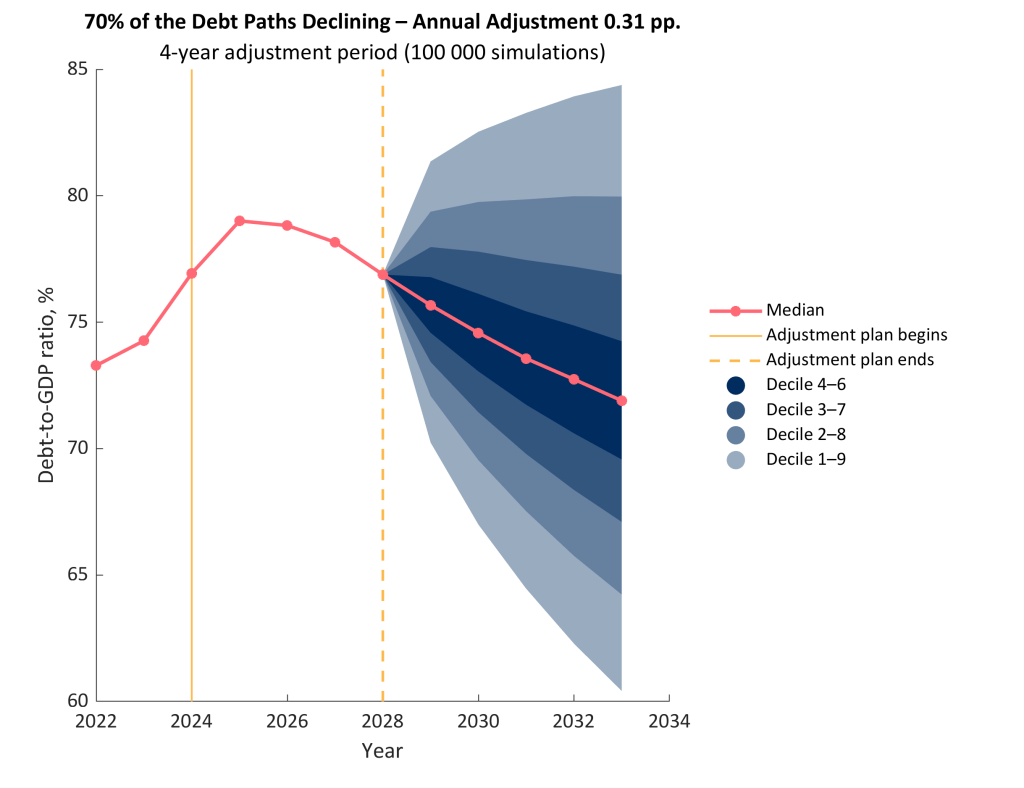

| Baseline trajectory (Figure 2) | 0.42 | No | 70% | BS |

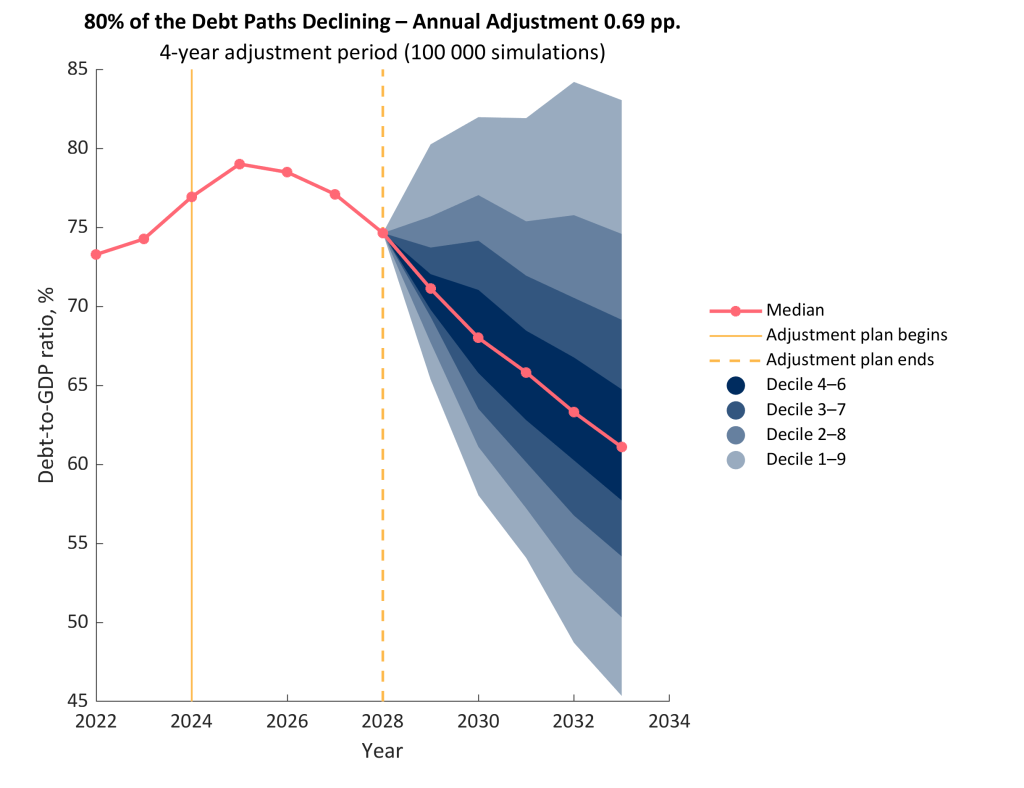

| Baseline trajectory (Figure 3) | 0.69 | Yes | 80% | BS |

As regards the reformed debt rules, the credibility level to be applied in the analysis is not yet certain at the time of writing. As can be seen from the calculations, the credibility level selected has a significant impact on the adjustment need produced by the scenario that takes uncertainty into account.

A scenario that takes uncertainty into account makes the required annual adjustment need more stringent. With the 70% credibility level used by the Commission, the annual adjustment need is around 0.3 percentage points (Figure 1). Translated into euros, this is roughly EUR 0.9 billion.

The short adjustment plan means that the public finances in Finland must be adjusted considerably

None of the above scenarios is sufficient to meet the debt sustainability safeguard set for the debt ratio. For this reason, the required adjustment is determined in such a manner that the debt ratio will decrease during the adjustment period by the 2 percentage points required by the safeguard.

In the scenario that takes uncertainty into account and that is based on the 70% credibility level used by the Commission, the debt ratio does not decrease at all during the adjustment period (Figure 1). When the annual adjustment is raised to 0.68 percentage points, the debt ratio decreases by more than 2 percentage points. In this case, the credibility level also rises to 90% (Table 1).

Compliance with the safeguard therefore requires an adjustment of 0.68 percentage points. This means an annual adjustment of EUR 2 billion, which is a significant requirement.

The length of the adjustment plan has a significant impact on the annual fiscal adjustment

It is not advisable to implement large fiscal consolidation in a period of four years.

Understanding of the wider long-term negative effects of large fiscal consolidation has only started to increase. Research related to this has been carried out by, for example, Fetzer (2019), Gabriel et al. (2023) and Cerra et al. (2023).

A large fiscal consolidation should therefore be spread over a sufficiently long period of time. The reformed debt rules take this into account by providing an opportunity to obtain an extension to the four-year adjustment period. The maximum extension is three years, in which case the adjustment period is seven years.

The extension may reduce the annual adjustment need considerably. This is because, in practice, the extension spreads the same adjustment over a larger number of years.

Finland’s annual adjustment need could fall to 0.2 percentage points if the adjustment period were seven years (Bruegel, 2023). This means an annual adjustment of around EUR 0.6 billion. The possibility of a three-year extension has not (yet) been examined in the calculations made by the fiscal policy monitoring function.

Safeguards complicate the reformed framework unnecessarily

According to Bruegel (2023), the debt sustainability safeguard for the debt ratio would only be binding on two countries: Finland in the case of a four-year adjustment period and Spain in the case of a four and a seven-year adjustment period. For all other countries, the debt sustainability analysis produces a reference trajectory that also meets the debt sustainability safeguard.

Instead of additional safeguards, a better option would have been to modify the debt sustainability analysis. This could have been achieved in a number of different ways, and it would have made the debt sustainability analysis less complicated. Now the safeguards complicate the analysis unnecessarily.

One solution would be a technical change in the assumptions of the debt sustainability analysis.

The Commission’s analysis assumes that positive and negative deviations in the economic growth, interest rate and primary balance forecasts are equally probable in the scenarios that take uncertainty into account. This leads to a symmetrical distribution of the simulated debt paths as shown in Figure 1.

However, this assumption is not realistic. On the other hand, an assumption that deviations are based on actual observations of the forecasted variables result in an asymmetrical distribution of the simulated debt paths as shown in Figure 2.

To simplify, the asymmetry is explained by the fact that, after negative deviations, the following simulated observation is also likely to be negative. There is no similar phenomenon with positive observations. For this reason, the probability of simulated paths with high debt ratios is higher with the latter method than with the former one.

The observed asymmetry of debt paths is also more broadly linked to the asymmetry of cyclical fluctuations. Upturns are steady and persistent, whereas downturns are sudden and non-persistent (Dupraz ym., 2023).

With a small change, the debt sustainability analysis can be modified in a more realistic and data-based direction. This method meets the safeguard when the credibility level is raised from the 70% used by the Commission to the 80% used by the IMF (Figure 3).

A broader social debate on the EU debt rules would be desirable

The purpose of this blog post was to illustrate the future content and operation of the debt sustainability analysis and its relationship with the indicator to be followed, i.e. the net expenditure path. The details of the debt sustainability analysis may still change, but the operating principles will remain unchanged.

The EU’s reformed debt rules will steer the Member States’ fiscal policy and fiscal space significantly. It would therefore be desirable to have a broader social debate on such a significant reform.

Sources

Bruegel. (21 December 2023). Assessing the Ecofin compromise on fiscal rules reform (Opens in a new tab).

Cerra, V., Fatás, A., & Saxena, S. C. (2023). Hysteresis and Business Cycles (Opens in a new tab). Journal of Economic Literature, 61(1), 181–225.

Dupraz, S., Nakamura, E., & Steinsson, J. (2023). A Plucking Model of Business Cycles. Working Paper.

Fetzer, T. (2019). Did Austerity Cause Brexit? (Opens in a new tab) American Economic Review, 109(11), 3849–3886.

Gabriel, R. D., Klein, M., & Pessoa, A. S. (2023). The Political Costs of Austerity (Opens in a new tab). The Review of Economics and Statistics, 1–45.

IMF. (2022). Staff Guidance Note on the Sovereign Risk and Debt Sustainability Framework for Market Access Countries (Opens in a new tab) [Policy Paper].

More information