One of the core ideas in sustainable development is applying a long-term perspective to take account of the famous ‘future generations’. Applying a long-term perspective is not easy but makes it possible to address risks that are unlikely to be realized in the short term, such as a pandemic or the climate change.

How could we incorporate the long-term perspective into the strategy and planning cycles currently applied in public administration? Let us take a look, by way of example, at the different approaches that the European Commission and the Finnish Government have taken to implementing the UN’s 2030 Agenda. The EU decided to prepare no strategy, whereas the Finnish Government based its sustainable development strategy, issued as a Government report, on its existing Government Programme. It seems that in both cases it is very difficult to introduce new initiatives in the middle of the programme period.

The article is based on a performance audit conducted by the National Audit Office of Finland and on a rapid case review by the European Court of Auditors.

The Agenda sets goals for the year 2030

Taking account of the future generations was one of the key themes already in the report ‘Our Common Future’, issued by the UN’s Brundtland Commission in 1987. The term ‘sustainable development’ was actually introduced in the Brundtland report.

In recent years, the global sustainable development policy has focused more on the integration of the different dimensions of sustainable development – the environmental, social and economic dimension – than on the long-term perspective. However, future generations are also mentioned in the 2030 Agenda documents. In addition, some of the sustainable development goals (SDGs) that serve as the framework in the 2030 Agenda set concrete targets for the year 2030. Examples of these are ending extreme poverty, free primary and secondary education for everyone, and sustainable and efficient use of natural resources.

When the UN adopted its resolution on the 2030 Agenda in 2015, the time span for the goals was 15 years. Although this exceeds conventional budget or five-year cycles, it does not extend beyond generations. Nevertheless, it is not easy to incorporate the 15-year perspective into the strategies of public administration.

Incorporating the 2030 Agenda into the EU’s planning cycles has not been easy

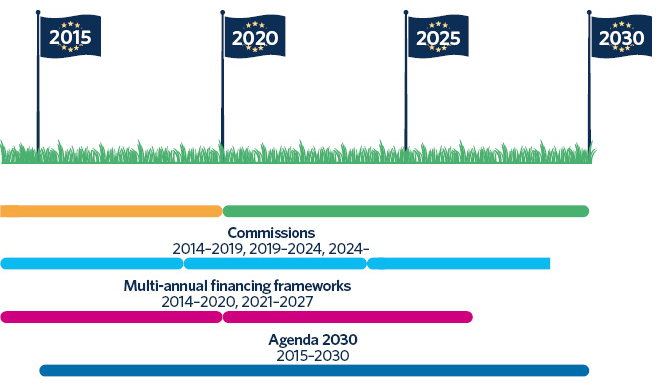

One year after the adoption of the 2030 Agenda, the European Commission published a communication on the issue. The Commission stated that it would address the SDGs with the Europe 2020 Strategy, which had been issued already in 2010, i.e. five years before the 2030 Agenda. Thus, the Commission did not consider it necessary to revise its strategy. Many of the EU’s goals, such as the policies aiming to reduce greenhouse gas emissions, were in line with the goals set by the 2030 Agenda. However, a significant drawback was that there was a gap of ten years between the EU 2020 Strategy and the 2030 Agenda.

The European Parliament, the European Council and the Council of the European Union urged the European Commission repeatedly to prepare a strategy for implementing the 2030 Agenda. In 2019, the Commission finally issued a reflection paper, where the Juncker Commission (2014–2019), whose mandate was about to end, settled for outlining alternative actions for the next Commission. No strategy for the implementation of the 2030 Agenda was thus prepared for the EU in 2019, either.

The timing of the 2030 Agenda was difficult in view of the EU’s own planning (Figure 1). The period of the EU Strategy for 2010–2020 was only halfway through, and it was still early days for the multi-annual financial framework for 2014–2020. Adding new goals would have been difficult in this connection. On the other hand, it seems that there is never a good time to prepare such a long-term strategy. For example, the European Court of Auditors pointed out that the new EU funding period for 2021–2027 was prepared with no support from a common EU strategy.

At the beginning of 2020, the Commission issued a new strategy, the Green Deal, for 2021–2030. It includes a long-term commitment for 2050, when the EU should be carbon neutral. According to the Commission, the Green Deal is an essential part of the Commission’s strategy for implementing the 2030 Agenda. However, it remains unclear what the other parts of the strategy are.

The Finnish Society’s Commitment to Sustainable Development was updated to comply with the Agenda 2030

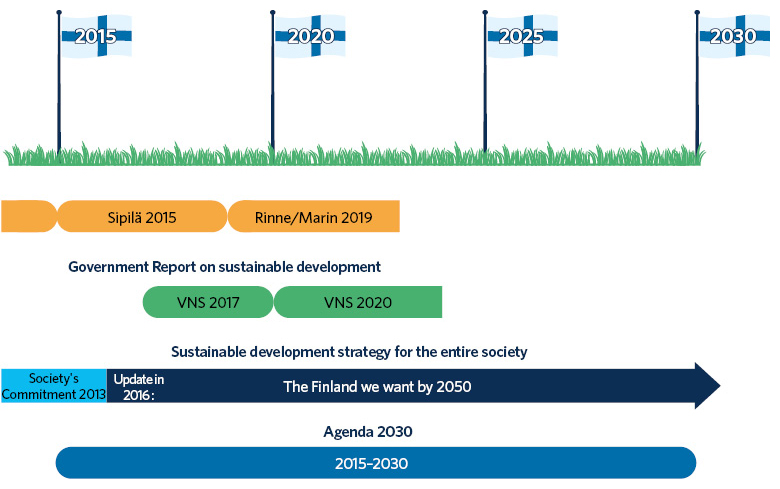

Finland revised its national strategy for sustainable development in 2013. The new strategy was prepared by the Finnish National Commission on Sustainable Development, which is an influential forum that is led by the Prime Minister and that gathers together different societal actors. The National Commission formulated the sustainable development strategy as Society’s Commitment to Sustainable Development, ‘The Finland we want by 2050’.

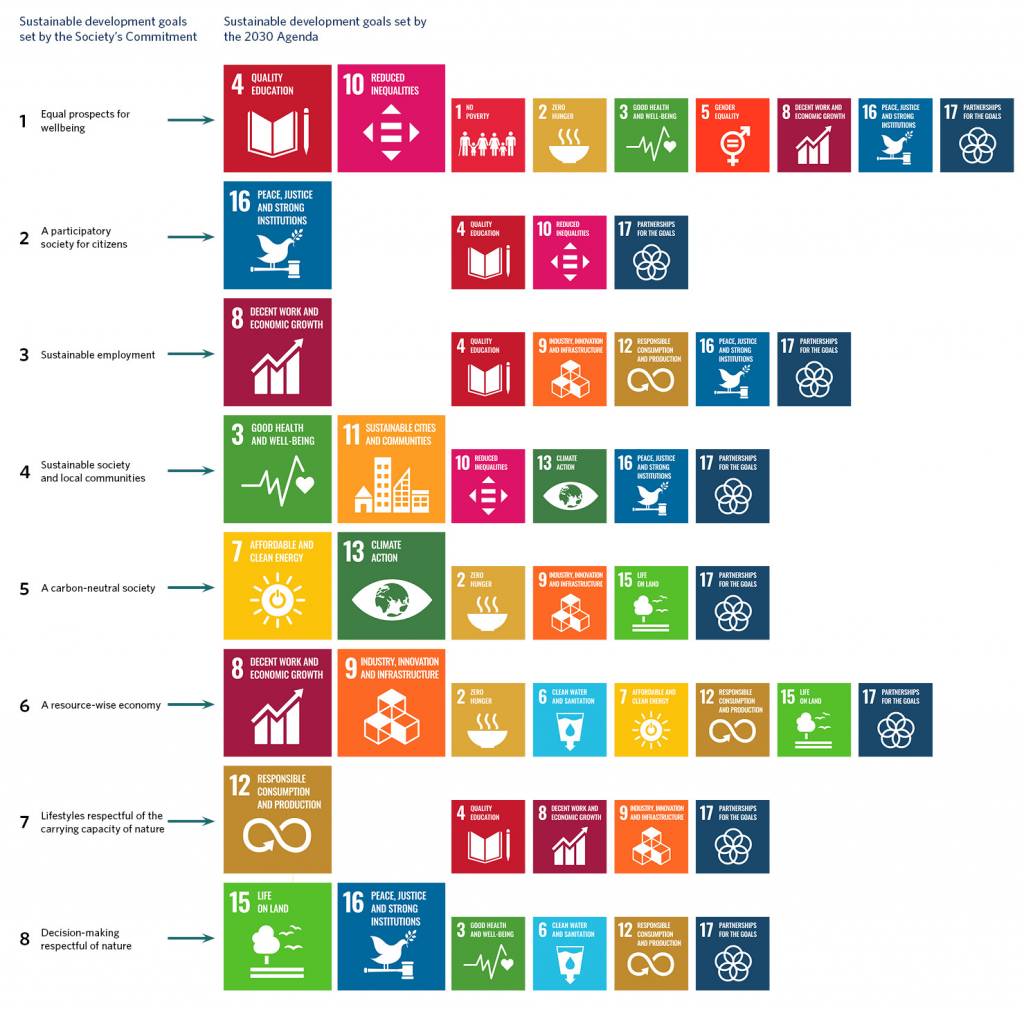

The Society’s Commitment was issued two years before the UN adopted its resolution on the 2030 Agenda. When the 2030 Agenda had been adopted, the Finnish National Commission on Sustainable Development updated the Finnish Society’s Commitment to comply with the policy lines set by the Agenda. The Finnish sustainable development strategy is thus largely in line with the UN documents. The eight goals included in the Commitment cover fairly well all 17 main goals of the 2030 Agenda. At the same time, the Finnish Society’s Commitment is very extensive, and the goals it sets are very general in nature. The Commitment sets no target levels for the goals. Therefore, the goals are in fact directions in which to proceed rather than objectives whose achievement could be assessed.

The Government Programme restricted the presentation of new measures in the report

The principle for the implementation of the 2030 Agenda is that all states decide themselves on their national goals, which should be steered by the global goals. The states also decide how to incorporate these goals into their national plans. The Finnish Government issued a report on sustainable development (In Finnish: VNS 1/2017 vp.) in 2017. The report disclosed how the Government was going to implement the 2030 Agenda in its own operations.

However, the report presented hardly any new measures. This was because the report was drawn up in the middle of the Government term. Therefore, the measures described in the report had to either comply with the Government Programme or be such that they would be implemented in any case.

The report presented three ways of spanning Government terms. First, it selected two focus areas for the Finnish sustainable development policy: ‘carbon neutral and resource-wise Finland’, and ‘non-discrimination, equality and a high level of competence in Finland’. The idea was that these focus areas could be more permanent and independent of Governments, and that they could thereby possibly apply until 2030.

Second, the report of 2017 defined policy principles for the implementation, i.e. how the efforts should be taken. The policy principles should also steer all decision-making to a more sustainable direction. According to the report, Prime Minister Sipilä’s Government proposes that the principles of ‘long-term action and transformation’, ‘policy coherence and global partnership, and ‘ownership and participation’ should extend beyond government terms. In the report, the policy principles were considered to extend beyond government terms although the previous Government obviously could not decide this.

Third, the report also described a procedure for monitoring and evaluating sustainable development even during the following Government terms. The monitoring system is based on indicators that provide information to be evaluated annually. In addition, since 2018, the Government has reported on sustainable development to Parliament in its annual report. The problem is that the indicator system does not fully correspond to the goals set. The Government has, moreover, reported only very briefly on how it has implemented its own strategy, i.e. the report it issued in 2017. On the EU level, Eurostat, in turn, publishes monitoring data on the achievement of the SDGs, although the EU has no strategy for the 2030 Agenda. Some of these indicators are related to the EU’s policy objectives, such as the EU 2020 Strategy.

The Government Programme is binding on other plans

The binding and detailed nature of the Government Programme proved to be clearly problematic when the Government Report of 2017 was prepared. New measures could not be taken even though the report was based on the UN’s resolution on the 2030 Agenda, which is binding on all states. On the other hand, the Report managed to raise three themes intended to extend beyond Government terms: nationally important focus areas, policy principles for steering preparation and decision-making, and a monitoring and evaluation system.

Furthermore, the Government Report (2017) probably had an effect on the preparation of Rinne’s and Marin’s Government Programmes, as their formulation clearly highlighted sustainability. This was successful, as the phrase “a socially, economically and ecologically sustainable society” was included even in the title of the Programmes.

The present Government is also planning to issue a new report on sustainable development in 2020.

Although sustainability is mentioned even in the title of the Government Programme, the circumstances have remained unchanged: the sustainable development policy is made under the present Government in a situation where the Government Programme is long and dictates the measures to be taken during the Government term in detail. There seems to exist a recurrent process where new programmes react to previous ones but do not enable agile reaction to new issues emerging from outside the Government Programmes.

It is crucial for the success of the sustainable development policy that the four-year Government Programme takes adequate account of long-term sustainability instead of focusing only on the situation during the new Government term. Longer-term sustainability problems, such as the consequences of the climate change, can also have acute impacts on society through epidemics and severe meteorological phenomena, for example. The Government Programme should thus be sufficiently generally formulated to leave room for responding to unexpected crises.

In addition to the measures included in the programmes, it is also important to change the ways of operating. The different dimensions of sustainable development, the intergenerational perspective, as well as inclusiveness should be given more consideration in all policy preparations. It is important to monitor, evaluate and report on how the dimensions of sustainable development are taken into consideration as well as the change in the ways of operating. The reported data should also be utilized clearly more than at present.

Sustainable development provides a broader framework for shorter-term programmes

Taking sustainable development and future generations into account poses a challenge to public administration and its planning cycles. Although the EU is making an ambitious policy in many areas of sustainable development (most recently in its Green Deal programme), it has not been able to profile itself as a credible actor in implementing the 2030 Agenda.

Unlike the EU, Finland reacted relatively rapidly to the UN’s 2030 Agenda. The Finnish National Commission on Sustainable Development adapted the Society’s Commitment to comply with the goals set by the Agenda, and the Government issued a report on the measures it had taken based on the Agenda. The entire sustainable development process seems to have gained momentum from the UN’s SDGs. Based on an audit conducted by the National Audit Office of Finland, the Finnish public administration seems to be more familiar with the global goals than the national ones, which were actually set earlier. The audit showed that the national goals had only little impact on the ministries’ operations.

In the EU, it is difficult to introduce new initiatives in the middle of a strategy or funding period, while in Finland, it is difficult to introduce new initiatives that are not included in the Government Programme. However, it seems to be possible to influence the ways of operating and the contents of the following programme periods by the sustainable development processes.

At best, the long-term perspective can make it easier to identify problems such as the coronavirus crisis; the possibility of a pandemic has in any case been generally known. The long-term perspective could also make it easier to deal with other risks that might paralyze societies, such as the impacts of the climate change – both globally and in Finland.