Infrastructures, such as ICT systems, transport infrastructure and building stock, are an important part of the government’s fixed assets. The lifecycle management costs arising from infrastructure maintenance and repair backlog should be comprehensively presented in the budget proposals and the General Government Fiscal Plan together with new investments and acquisition costs. Common goals, acquisition and management procedures as well as monitoring practices are also needed for the lifecycle management of fixed assets.

Sustainable financing solutions are needed for the lifecycle management of the information systems used by central government and wellbeing services counties

It is stated in the audit of central government information systems that the lifecycle perspective of information systems is recognised in central government but no common objectives have been set for their lifecycle management and there are no established practices for monitoring their repair backlog.1 Successful lifecycle management of an information system requires that long-term planning starts at the system purchasing stage, and that risks arising from the ageing of the system are identified and managed. Factors affecting the maintenance costs of information systems, such as frequent updates, technological changes and end-of-life costs of the system, must also be taken into account. In principle, the budgetary process and the General Government Fiscal Plan provide a framework for the meeting of continuous maintenance and development needs as funding for the following four years can be proposed under the General Government Fiscal Plan. However, according to the audit findings, central government’s funding solutions do not adequately support system lifecycle management, as the funding for the systems is based on short-term plans and priority is given to new technology projects. As the value of automation cannot be calculated, the productivity potential of the systems is difficult to demonstrate when applications for funding are submitted. Moreover, a system to be decommissioned does not generate any savings for the financing of a new system.1

Developing the digitalisation and information management of the wellbeing services counties is estimated to cost between two and three billion euros over the next ten years. Well-functioning healthcare and social welfare services can be provided more efficiently with customer-oriented and reliable information systems as well as online and mobile services. This is expected to slow down the growth in healthcare and social welfare expenditure even though no specific savings targets have been set.

The healthcare and social welfare funding allocated to wellbeing services counties for ICT changes and digitalisation in 2021 and 2022 was examined in the audit.2 Based on the audit, the counties were able to make the necessary changes to their ICT systems by the beginning of 2023, despite a shortage of experts and delays in the awarding of government grants. However, only a small number of wellbeing services counties had comprehensively included the costs arising from client and patient information systems in their investment plans. ICT investments accounted for about one billion euros of the planned investments presented by the wellbeing services counties in autumn 2022. This is about 11 per cent of all investment needs presented by the wellbeing services counties. According to the audit findings, the ICT costs of healthcare and social welfare will increase in nearly all wellbeing services counties over the next few years.2

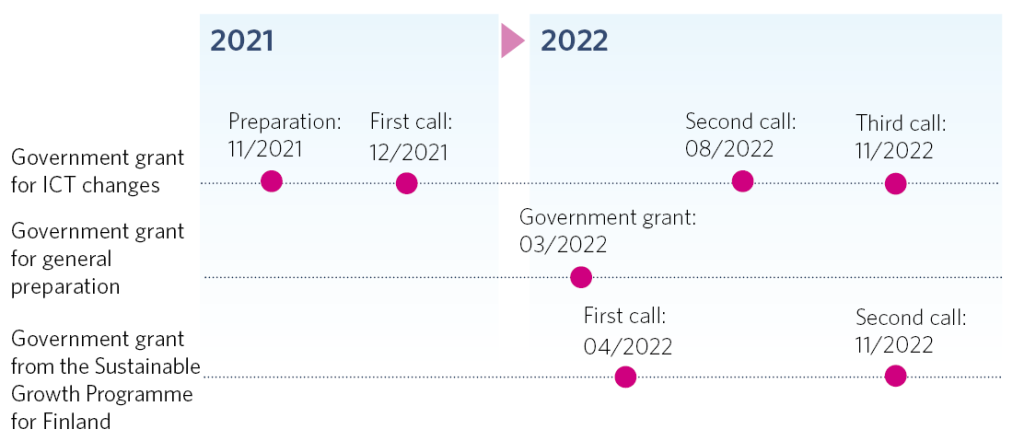

A total of nearly EUR 700 million in government grants was awarded to the ICT change and digitalisation of healthcare and social welfare in 2021 and 2022. Grants from three different budget items were awarded on seven occasions (Figure 1, Table 1). However, only some of the government grants awarded under the Sustainable Growth Programme for Finland were earmarked for the development of information management and digital services. The government grant package was built in stages in accordance with the latest situational picture. Some of the government grants were awarded on the basis of imputed criteria and some of the wellbeing services counties received discretionary funding.2

Based on the audit, the criteria used to assess the government grant applications submitted by wellbeing services counties were not entirely transparent. For example, the application criteria were changed in the middle of the application process. There have also been overlaps in government grants for ICT change, both in terms of timing and content. Some of the grants budgeted in the Sustainable Growth Programme have also remained unused due to the strict eligibility criteria. According to the audit conclusions, a project-type funding model based on applications for government grants does not promote long-term implementation of ICT change or development of digitalisation. The activities should be steered through a single funding channel and by a single government grant authority so that the wellbeing services counties could carry out their ICT development work on a long-term basis.2

| Government grant | Budget item | 2021 | 2022 | Total |

| ICT change | 28.70.05 | 215 165 200 | 124 688 372 | 339 853 572 |

| General preparation* | 28.89.30 *of which allocated to ICT change (estimate) |

(62 019 000) – |

155 845 832 (66 790 149) |

155 845 832 |

| Sustainable Growth Programme for Finland (RRP) |

33.60.61 | – | 289 181 576 | 289 181 576 |

| Total | – | 215 165 200 | 569 715 780 | – |

Supplier dependency can become a risk for the lifecycle management of information systems

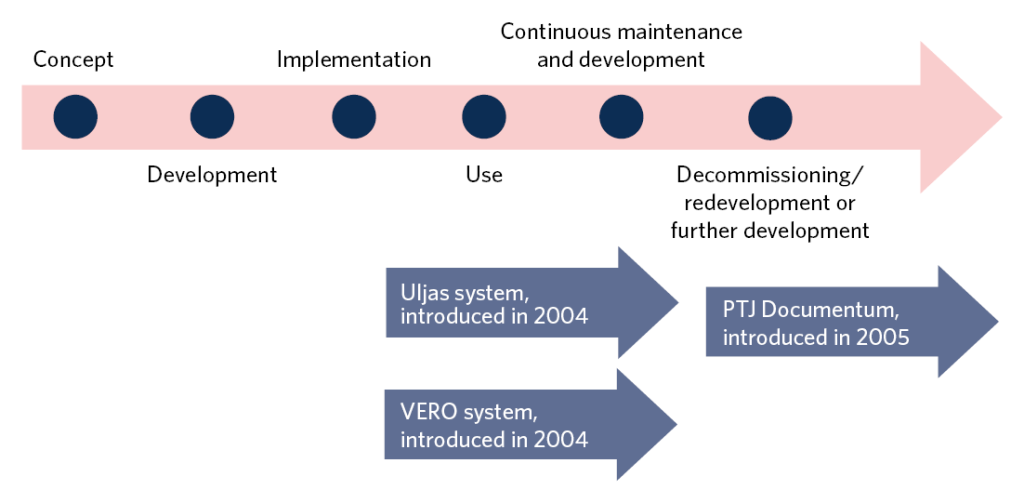

The long lifecycle of an information system can be a sign of successful system design, long-term maintenance and continuous development. The long lifecycle may also be due to supplier dependency, delays in the acquisition and introduction of the new system, or the fact that there has been no need for major changes in system-related functions and processes. Supplier dependency means that a customer has undertaken to use the technology of a specific supplier and as a result, the customer has less discretion in selecting new suppliers during the system lifecycle.

Three central government information systems were selected for the National Audit Office’s case audit, one of which is in use throughout the Government and two of which are used in government agencies in a specific administrative branch (Figure 2). All government agencies selected for the audit have sufficient expertise in the acquisition, contracting and management of information systems. Non-compliant contract procedures or material shortcomings in the information security of the systems concerned or in data processing controls were not identified in the audit.1

Based on the audit, supplier dependency may become a problem, especially in long-term information system agreements. It may also be difficult to withdraw from off-the-shelf solutions wholly in the possession of the supplier, which have become more common in recent years. Ways to reduce the risk of supplier dependency were examined in the audit. These include effective planning of the information system enterprise architecture, careful market research (also during system development) and using a negotiated procedure in competitive tendering. The procurement contract can be drafted in such a manner that sufficient intellectual property rights to the system remain with the customer. However, the terms and conditions governing intellectual property rights in long-term information system contracts may be difficult to interpret or be unfavourable for the customer. Over time, it may also be difficult to find out what amendments have been made to the contracts and to establish the relationship between different contracts and their precise content. Recently recruited staff members may also be less familiar with the content of the contracts concluded by their predecessors. The risk of supplier dependency can also be reduced by joint service purchases.1

Joint procurements of services can save time and costs

In joint procurements, goods or services are purchased for more than one contracting entity at the same time. Joint purchases can generate direct or indirect cost savings and potentially higher-quality products. It was concluded in the audit (10/2020) that government agencies had mostly complied with the joint purchasing obligations but they did not have any uniform understanding of which products and services are covered by the joint purchasing obligation. The joint purchasing obligation applies to such items as computers and IT equipment, their parts and accessories but not to information system purchases. The monitoring of joint purchases was hampered by the fact that financial administration automation of joint purchases made by government agencies worked in the Handi system in the same way as in other purchases, and the purchases were not registered separately in the system. Furthermore, Hansel Ltd, which is responsible for the joint purchases, had assessed the economic, social and environmental responsibility of joint purchases but had not conducted sustainability audits because of the effort and costs involved. Based on the audit follow-up, more detailed specifications for the products and services covered by the obligation have been introduced, and development work on joint purchases has been carried out. Accounting offices are now able to monitor their purchasing contracts from a centralised information system. The decisions on the introduction of responsibility audits will be made in spring 2023.3

Wellbeing services counties are able to make purchases from their own inhouse companies without competitive tendering if the company generates a maximum of 5 per cent or EUR 500,000 of its turnover outside its owners and the owners exercise control over the company. Based on the findings of the audit of the digitalisation of healthcare and social welfare, wellbeing services counties utilised their inhouse companies in the purchases of ICT services during the transition phase. Some of the wellbeing services counties were of the view that inhouse companies were practically the only way to transfer the responsibility for organising the services in a secure manner within the timetable laid down in legislation and to ensure sufficient competence in the implementation of ICT changes. Based on the audit, inhouse companies were considered by the wellbeing services counties to be both important partners and problematic to steer.2

Nationally produced digital services are essential for the interoperability of the information systems used by wellbeing services counties

DigiFinland Ltd develops national digital service solutions, especially for wellbeing services counties. The company was established in 2020 by merging SoteDigi Ltd and Vimana Ltd, two state-owned special assignment companies. The ownership structure of the company changed at the beginning of 2023 when the state transferred some of the company’s shares without any consideration to the wellbeing services counties, the City of Helsinki and the HUS Group. The Finnish state still retains about one third of ownership and voting rights in the company. The company’s funding is based on fees collected from its customers, and separate funding for major development projects is applied for from the government. Wellbeing services counties are not obliged to use the services supplied by DigiFinland and the company cannot provide services to municipalities or joint municipal authorities.

Kanta services are national digital services essential for the interoperability of healthcare and social welfare information systems. The fees collected from the users of Kanta services cover about half of the maintenance and development costs, and the other half comes from the Budget. Kanta services comprise several services that are at different stages of their lifecycle and there are also significant service-specific differences in terms of utilisation.

The added value that the digital and Kanta services provided by DigiFinland Ltd bring to the wellbeing services counties were assessed in the audit.2 Based on the audit findings, the wellbeing services counties see potential in DigiFinland’s operations when the services offered by the company meet client needs and are cost-effective compared to other services available. However, the counties have different starting points and different levels of digital competence, which is not the best basis for developing uniform national-level services. At the same time, wellbeing services counties must first introduce Kanta services in their own client and patient information systems before the information is available to end users through Kanta. Thus, the end user’s experience of the services also depends on how the client and patient information systems of the wellbeing services county have been implemented.2

The key principles of communication that must be followed by the providers and producers of information system services are set out in the Client Data Act and other regulations. The systems must also meet the key requirements concerning interoperability, information security, data protection and functionality. Even though there have been improvements in Kanta services at general level, the objectives concerning their use and utilisation set out in the Client Data Act have not been fully met. At local level, the introduction of the functionalities offered by Kanta services has been slowed down by the waiting for the healthcare and social welfare reform and, in particular, uncertainty about the source of funding for the system development work. With regard to law enforcement, the problem is that individual actors do not always report deviations to the authorities as required under the Client Data Act.2

The wellbeing services counties are also responsible for emergency medical services. In the audit (9/2019), the absence of uniform national statistics on emergency medical services and indicators describing the activities was identified as an obstacle to resource planning in emergency medical services. Based on the audit follow-up, the knowledge base for emergency medical services is being developed so that the data in the ERICA emergency response centre system and the KEJO system used by the authorities can be combined in a manner that allows the data to be used for such purposes as the planning of resources for emergency medical services. The aim is also to integrate information on emergency medical services and treatment chains into the data production line of emergency medical services from the Kanta service’s patient information archive, information management service and the care notification system Hilmo.4

Recommendations of the National Audit Office for the lifecycle management of information systems and digital services

Investments and costs required to manage the lifecycle of the information systems used by the authorities should be included in the preparation of the Budget. The funding required for major ICT reforms should be taken into account in central government spending limits and budgets to enable long-term system lifecycle management.1, 2

Uniform practices boosting productivity in such areas as the prioritisation of technologies, management of supplier dependency risk and funding of system development needs1 are needed in the lifecycle management of central government information systems.1

National digital healthcare and social welfare services should be coordinated so that they meet the needs of wellbeing services counties. Digital services should be developed systematically and on a long-term basis.2

Maintaining the infrastructure and fixed assets under the responsibility of the government requires continuous lifecycle management and a long-term approach to the planning of investments

According to the findings of the audit (8/2016), the aid for and investments in broadband construction and projects have not been sufficient to safeguard the continuity of the operations of broadband companies. It was also found that participation in the aid programme projects had negatively impacted the finances of many of the participating municipalities. It was found in the first audit follow-up phase in 2020 that the impacts of the Broadband for All projects had not been sufficiently monitored and some of the projects of the Fast Broadband aid programme that ended in 2022 had negatively impacted the financial situation of key stakeholders. For this reason, the National Audit Office deemed it necessary to supplement the follow-up with a second follow-up in 2023. Based on the second follow-up, the monitoring of the aid programme has been improved and the financial impacts have been taken into account in the development of the programme and the associated legislation. An ex-post assessment of the aid programme has also been carried out. It was concluded in the follow-up that the aid programme has not caused any unreasonable financial losses to stakeholders. The municipalities providing funding for the projects have estimated that the aid programme had positive impacts on their vitality. Extensive investments in sparsely populated areas and areas outside built-up areas constituted a significant financial burden for the companies and cooperatives that had carried out the projects (especially in the early years) but the financial situation of the companies has improved since the end of the aid programme.5

It was recommended in the audit (12/2020) that when decisions on transport infrastructure investments are made, more consideration should be given to the impacts of new investments on infrastructure maintenance needs and the resulting maintenance and repair costs and that the financial assessment of transport infrastructure repairs should be developed so that the measures can be compared and prioritised in a transparent manner. Based on the audit follow-up, the performance agreement of the Finnish Transport Infrastructure Agency sets targets for the overall economic and long-term management of the transport infrastructure, for improving the efficiency, quality and market performance of transport infrastructure management and for focusing transport infrastructure management measures according to customer needs and the state of the transport infrastructure.6 Indicators and target levels have also been specified and they are monitored. Infrastructure maintenance costs are also included in budget proposals. It is required in the guidelines for preparing the 2024 Budget that an assessment of the cost impacts of transport infrastructure investments (development projects) should be carried out. More consideration to the investments and maintenance as a whole is also given in the 12-year national transport system plan prepared for the period 2021–2032.

Based on the follow-up of audit 5/2020, government agencies now take a longer-term approach to the planning of their investments in machinery and equipment and the guidelines for planning and monitoring investments are now more specific than in the past. However, the long-term planning of investments is not systematically monitored in the procurement units or in the Ministry of Finance. Moreover, the investment plans for fixed assets for the coming years are not summarised in the Government’s financial plans. Even if the investment plan were not politically binding beyond the operational and financial planning period, long-term investment plans would give Parliament a more comprehensive picture of the expected trends in central government investment expenditure.7

Based on the findings of audit 14/2020, there was a solid basis for effective lifecycle management of central government building assets, as legislation promotes high-quality construction, management and maintenance of the building stock and creates an opportunity for using lifecycle costs as a basis for assessing costs in purchases and investment decisions. The state real estate strategy also aims to examine the lifecycle impacts of building assets comprehensively from different perspectives of the government’s overall interest, and the government’s premises strategy supports good building lifecycle management. The Ministry of Finance monitors the implementation of the strategies overhauled in 2021 with the help of the advisory boards it has appointed. It was recommended in the audit that the Ministry for Foreign Affairs should have established operating methods supporting the lifecycle management of properties located outside Finland and monitor their effectiveness. Based on the audit follow-up, the Ministry for Foreign Affairs has, since 2022, commissioned needs assessments of the sites it owns and leases and in connection with them, the criteria for leasing and owning sites have also been examined. Decisions to give up sites can also be made on the basis of the needs assessments. The Ministry for Foreign Affairs also reorganised its property management as of 1 April 2022. The key objective of the reorganisation was to bring construction and property maintenance in the same unit so that the operations can be coordinated on a centralised basis. The Ministry for Foreign Affairs also launched cooperation with the Senate Group in 2022. The aim is to utilise the expertise of the Senate Group in different areas of property and facility management.8